Datafication

Access

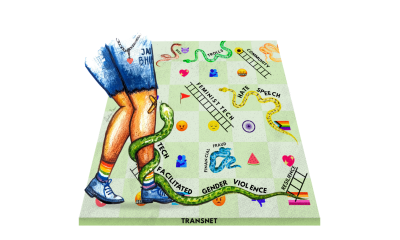

Online gender-based violence

Economy and labour

More about FIRN

The Feminist Internet Research Network focuses on the making of a feminist internet, seeing this as critical to bringing about transformation in gendered structures of power that exist on- and offline. Members of the network undertake data-driven research that provides substantial evidence to drive change in policy and law, and in the discourse around internet rights. The network’s broader objective is to ensure that the needs of women, gender-diverse and queer people are taken into account in internet policy discussions and decision making.