Alternate realities, alternate internets: African feminist research for a feminist internet

For the past decade, internet connectivity has been praised for its potential to close the gender gap in Africa. Among the many benefits of digitalisation, digital tools enable groups that are marginalised across the intersections of gender, race, sex, class, religion, ability and nationality to produce and access new forms of knowledge and conceive counter-discourses.

However, the internet, once viewed as a utopia for equality, is proving to be the embodiment of old systems of oppression and violence. In order to understand experiences of African women in online spaces, this violence must be viewed on a continuum rather than as isolated incidents removed from existing structural frameworks. Discriminatory gendered practices are shaped by social, economic, cultural and political structures in the physical world and are similarly reproduced online across digital platforms.

The research focussed on lived online experiences of women living in five sub-Saharan African countries, namely Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Senegal, and South Africa, illustrating that repeated negative encounters fundamentally impact how women navigate and utilise the internet. This, in turn, strengthens the argument for a radical shift in developing alternate digital networks grounded in feminist theory.

The overall objective of this study was to understand the online lived experiences of women in five countries in sub-Saharan Africa, namely Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Senegal and South Africa.

Online gender-based violence (GBV) has been found to be just as damaging to women as physical violence. Women are more likely to be repeat victims of online GBV and are more likely to experience it in a severe form than men are. A report by The International Center for Research on Women mentions that few studies have estimated the prevalence of online harassment and abuse, but it ranges from roughly 33% of respondents in studies from Kenya and South Africa to 40% of adults in the United States.

In terms of response, violence against women online is often trivialised with poor punitive action taken by authorities, further exacerbated by victim blaming. While some countries, mostly outside Africa, have attempted to address online violence, through legal and other means, the enforcement of such measures has proven tricky due to a lack of appropriate mechanisms, procedures and capacity. In some instances, women who have had their information shared without their consent have even been punished by the law. Online GBV, like any other form of GBV infringes on women’s fundamental rights and freedoms, their dignity and equality, and impacts on their lives at all levels.

There is a major gap in data on the prevalence of all types of online violence against women and girls in low and middle-income countries. Furthermore, where this evidence is available, the data is not gender-disaggregated or does not take into account the intersectional impact on class, women with disabilities, refugee situations, or traditionally marginalised areas.

The overall objective of this study was to understand the online lived experiences of women in five countries in sub-Saharan Africa, namely Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Senegal and South Africa. The study also sought to document the prevalence, experiences, and responses to online GBV, also known as technology-facilitated violence against women.

Feminist methods of data collection and analysis

A cross-sectional study was carried out across Addis Ababa, Nairobi, Kampala, Dakar and Johannesburg. Both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods were used. A total of 3406 women (from 18 to 65 years old, who use the internet at least once a week) were interviewed face-to-face as part of a broad-based semi-structured quantitative survey.

Five focus group discussions of 10 women each were conducted as well as five in-depth interviews with women who self-reported as having experienced online GBV. Women were asked questions about their experiences online, their perceptions around online violence against women and their digital safety practices.

Convenient sampling was used to identify respondents for the quantitative survey, while purposive sampling was used to select participants for the focus group discussion and in-depth interviews. The five cities were chosen for the survey based on the high density of internet users within them.

One of the issues we often ran into was the terminology for online GBV. There is currently no universally accepted definition of online violence and similarly, translating and discussing this content into local languages such as Amharic lead to challenges in the research. The other issue that arose was a tendency for respondents in the in-depth interviews to under report on the extent of the violence they experienced or to disclose information on perpetrators. This may have been because respondents felt that they were revealing sensitive information, which also made them feel uncomfortable or embarrassed.

One of the issues we often ran into was the terminology for online GBV. There is currently no universally accepted definition of online violence and similarly, translating and discussing this content into local languages such as Amharic lead to challenges in the research.

The study population is not representative of the population of women in each country, since enrollment in the study targeted women who lived in either the capital city or a large metropolitan city, who use the internet at least once a week. Therefore, the results of the study are not necessarily applicable to the greater population of women in each country.

Furthermore, convenience sampling of individuals in the city could overestimate or underestimate the prevalence of online harassment. Victims of GBV might be more or less willing to talk to enumerators about their personal experiences.

Given the position of the researchers in Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia, the data in this paper is skewed towards experiences, interviews, and policies from Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia, compared to the other two countries in this report. Hence, the knowledge produced may not be representative and can be partial in our arguments and feminist politics. However, this study does contribute to the limited research published on this topic and it provides a basis for additional research that further explores online violence, as well as broad studies that employ more diverse sampling methods and techniques.

Ethical framework

Ethical approval for the research was sought from local institutional review boards or ethics review boards around the different countries where data was collected. Enumerators were trained in ethics and the protection of human subjects before data collection in all the five countries.

To ensure that sufficient information about the study was provided to the participants, and to give them the opportunity to voluntarily participate in the study, informed consent was obtained from the study participants before conducting the interview. This process also explained the purpose of the research, its objectives, voluntary participation, duration of the interview, confidentiality, benefits, and risks involved.

To ensure confidentiality, names of participants were not written anywhere on the study materials and enumerators were not allowed to share any information they collected about the participant during the research except with people on the research team. To cater for any risks and discomforts that would arise from the study participants due to sharing online GBV personal experiences, enumerators assured participants that they were not under any obligation to disclose any personal information they did not wish to. However, where a participant needed counselling after the interview, the team linked them with relevant authorities that they collaborated with in each of the five countries.

Findings

-

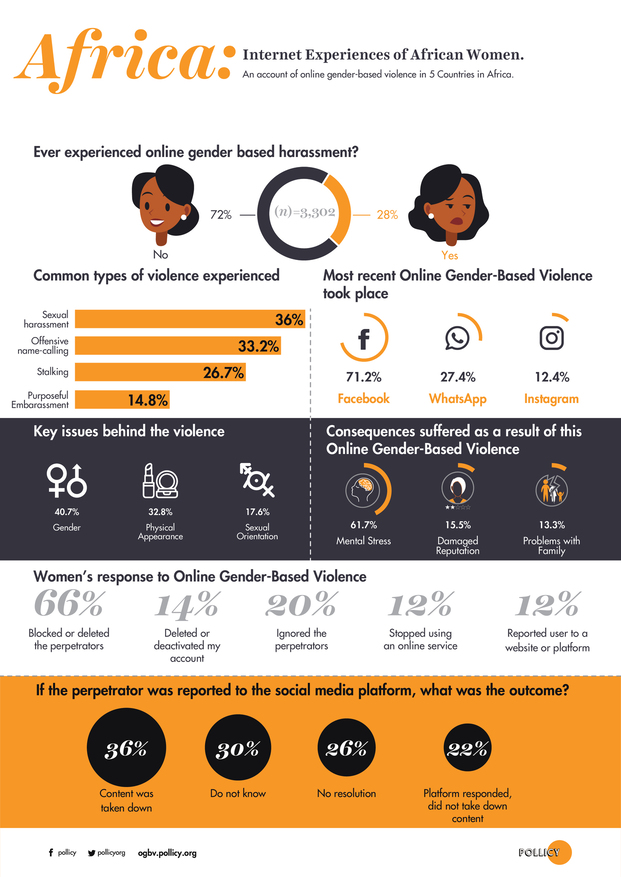

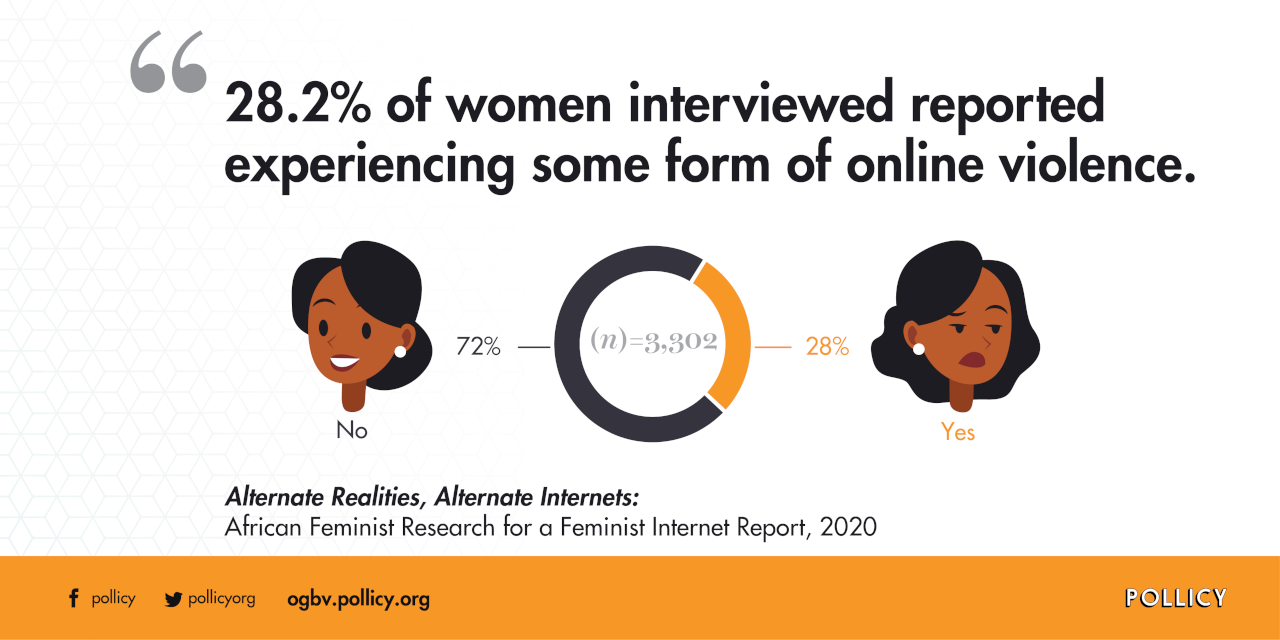

28% of the women responded that they had experienced some form of online violence.

-

The most common types of online GBV were sexual harassment (36%), offensive name-calling (33.2%) and stalking (26.7%).

-

71.2% of online GBV in the five countries took place on Facebook, followed by 27.4% on WhatsApp and 12.4% on Instagram.

-

61.7% of women interviewed reported suffering from mental stress and anxiety due to their experiences of online violence.

-

26.8% of the victims who reported their experiences to the social media platform where it had occurred, received no resolution to their complaint.

-

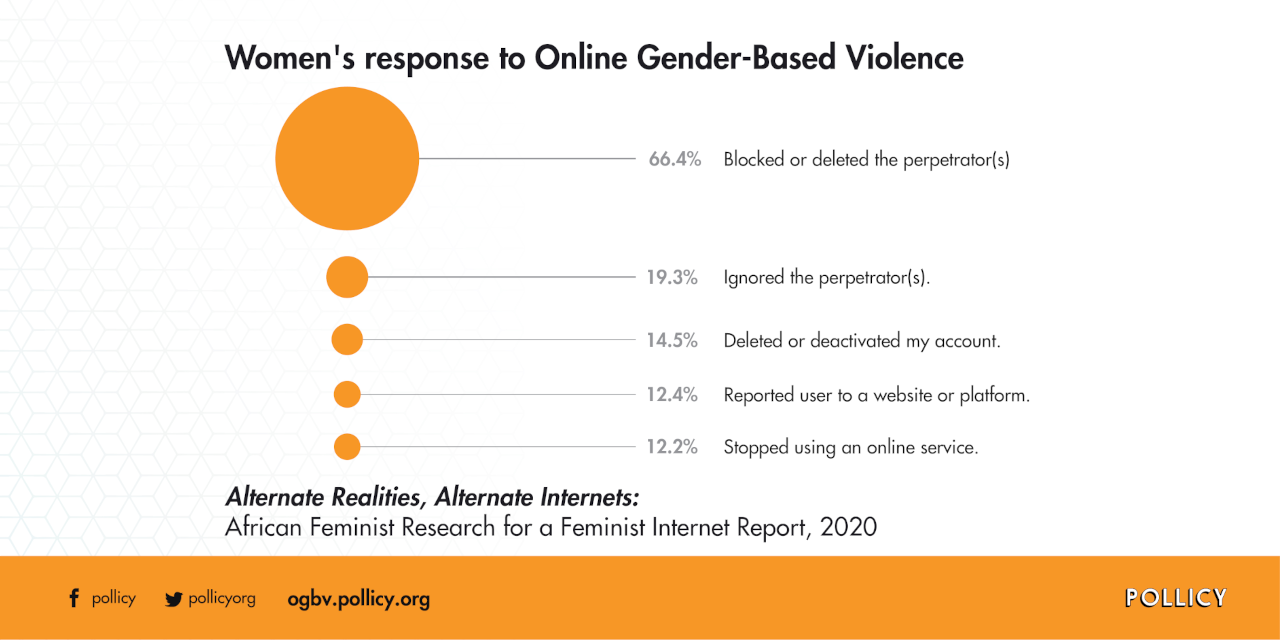

66.4% of women responded by blocking or deleting the perpetrator; 20.1% ignored the perpetrator and 14.5% deleted or deactivated their own accounts.

-

66.6% of the respondents who experienced online violence either did not know the identity of the perpetrator.

Policy and further research recommendations

There must be a strong focus on understanding how patriarchy manifests itself in online platforms and how to create a more feminist internet that gives women their full rights to internet access and freedom of expression.

The following are recommendations from the findings of the study:

- There should be stronger online harassment laws and increased focus and attention from law enforcement authorities. Law enforcement personnel must undergo gender-sensitive digital security training to address complaints of cyberbullying, cyber harassment, leaked private information etc. and to provide assistance, counselling and legal support to these women. In addition, advocacy and policy reforms to protect electronic and personal information should be considered.

- Better policies and tools from technology companies are required to enhance online safety for internet users. Foreign technology companies such as Facebook or Twitter should work with developers to create digital tools and products that are suited to local contexts and that can be accessed in local languages. Features should be easy to access, utilise and troubleshoot.

- Digital education in and out of schools is important to sharpen an individual woman's skills to know and understand the dangers of being online, how to innovate within the digital world as well as take precautions that the use of technology requires.

- Civil society must work to create awareness campaigns in local languages to highlight key issues around digital security to foster dialogue around safety when accessing the internet. It needs to conduct capacity building for women to improve their digital literacy skills through the use of free tools, to better understand online threats and to learn how to take action against these threats.

- There must be a strong focus on understanding how patriarchy manifests itself in online platforms and how to create a more feminist internet that gives women their full rights to internet access and freedom of expression.

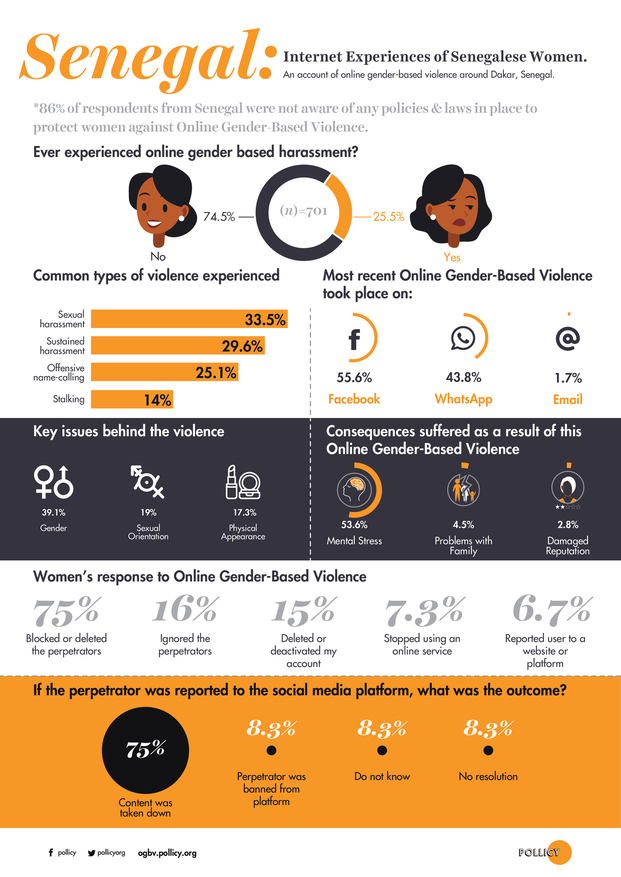

Infographics