Anti-rights discourse in Brazilian social media: Digital networks, violence and sex politics

Jair Bolsonaro's election as president of Brazil in 2018 capitalised on moral panics towards feminism and minority rights. Articulating gender, sexual difference, race and class, that hostility was increasingly felt on online digital networks. This research addresses the role of social media use and architecture in the production and dissemination of hate speech and anti-rights discourse as a fundamental aspect of the current right turn in Brazilian politics. In that context, it also explores emergent feminist and LGBT intersectional responses and struggles to define online violence.

Anti-feminist discourse and sex panics are fundamental pieces of the current conservative turn in Brazilian politics, whose apex was the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president of the republic in November 2018. We addressed the role of social media in public controversies over gender, sexuality and feminism in the period between the 2018 presidential election and the municipal elections in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Relentless attacks, whose semantics activate the intersection of gender, sexuality and race, often in the form of hate speech, operate as a form of political violence. Using mixed methods, we analysed digital engagement with anti-rights discourse in the Brazilian social media sphere and assessed the impact of this hostile climate on feminists, LGBTI people and their allies, as well as their individual and collective responses.

About the organisation and the research team

The Latin American Center on Sexuality and Human Rights (CLAM) is a regional resource centre based at the Institute of Social Medicine (IMS), University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). Created in 2002 as a transformation of the Program on Gender, Sexuality and Health, created in 1993 within the same academic unit, CLAM gathers UERJ faculty, graduate students, undergraduate trainees and associate researchers, and networks with feminist and gender and sexuality researchers, activists and professionals throughout Brazil and Latin America, mainly by means of its two online media sources: its website/ newsletter www.clam.org.br and its open-access academic journal www.sexualidadsaludysociedad.org. As gender and sexuality scholars, our teaching, research, dissemination work and partnerships favour a human rights perspective and intersectional approaches to different forms of social inequality.

This research was undertaken by Horacio Sívori, PhD, IMS professor, and Bruno Zilli, PhD, associate researcher, both social anthropologists in the field of sexuality studies. At different stages, Elaine Rabello, PhD, digital media researcher and formerly IMS professor, collaborated with digital research design; Tatiana de Laai, Phd, was workshop rapporteur and social media ethnographer; and Fabio Gouveia, PhD, Fiocruz researcher and faculty, curated our digital datasets. Jandira Queiroz, Brazilian civil society coordinator for Amnesty International Brazil, coordinated our workshop with prospective academic and activist partners. Maria Leão, PhD candidate at IMS, helped with the literature review. Roxana Bassi, with the APC tech team, developed our LimeSurvey instrument and stored its dataset; and Eliane De Paula, PhD, performed the statistical analysis of survey results. Silvia Aguião, PhD, CLAM and AFRO/CEBRAP researcher, acted as online interviewer.

While our earlier research had addressed digital network engagement with sexuality politics, our approach to feminist internet research began in 2008 when, in partnership with the Sexuality Policy Watch, we conducted a Brazilian case study as part of the APC WRP EROTICS project. Both those partnerships and the FIRN framework have been key in shaping our intellectual and institutional investments, reflection and engagement with gender, sexual politics, violence and the internet.

Our story

The broader thematic field of our research is that of gender and sexual politics. We discuss the struggles and the co-constitution, in the complex interplay of state and by civil society, of political identities and of subjects of rights. Over the past 12 years we have also invested in a socio- anthropological approach to the rapid changes in that field brought by the internet. The evolution of human-machine interaction does not only affect human beings and society, changing the way people behave, communicate and interact, but particularly the way science and politics are made. Witness to this are the current datafication of electoral processes and political advertising on social media and the research on the question of algorithmic racism, for example. The FIRN call made it possible to bring together our most recent investments in the study of the current conservative reaction to feminism and sexual rights in Brazil, on the one hand and, on the other hand, issues of feminism and sexual rights in relation to the grave regulatory challenges brought by the rapid transformations of the internet, particularly with regard to online violence. It was an opportunity to also face the methodological challenge of integrating digital research methods in our project design.

Both politically and theoretically, our project finds inspiration in intersectional approaches to issues of violence, vulnerability and feminist care, particularly by Black feminism and by feminist Brazilian alternative media. Related to those issues, another source of inspiration are the digital feminists who develop tech-age, grassroots frameworks and instruments for feminist internet security. The burgeoning field of Brazilian digital anthropology, with its focus on “thick data” is another permanent source of inspiration. Finally, we closely follow the works of Internet Lab, of Coding Rights, and of the Sexuality Policy Watch, main references in engaged research for the various intersections upon which our research pivots.

Some of those sources of inspiration came together at a live online panel we hosted in 2020, bringing together Brazilian feminist activists and academics to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic in the light of research on online violence and the current conservative turn in Brazilian politics.

Natália Neris, who coordinated two iterations of the research project Other Voices, with Internet Lab, spoke about the notable surge in online gender based violence against female politicians and feminist activists in the context of the 2018 election. At the time, social movements and feminists in particular became the targets of dehumanising violence on and offline. That was aggravated during the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting women’s safety and their very possibility of convening online.

Anthropologist Isabela Kalil, faculty at the São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics Foundation, who researches the anti-gender movement in Brazil, spoke about the co-constitution of the anti-gender agenda and neo-fascism in current national and global politics. She was precise at showing that present ultra-conservative forms of authoritarianism are not necessarily “anti-rights’’ or against democracy, but conceive of those values in a restrictive fashion that is threatened by the spectre of communism and gender.

Luísa Tapajós, member of the Brejeiras transfeminist dyke editorial collective, recalled the political assassination in March 2018 of Rio de Janeiro Councilwoman Marielle Franco, a Black bisexual feminist from the urban periphery, as a turning point in Brazilian feminist mobilisation. “That image of extermination inhabits us all,” she said. Later on the same year during the electoral campaign, the “Bolsonaro 17” electoral slogan was deliberately deployed and operated as a threat to lesbians visible in public spaces. Brejeiras’ response to that everyday fear was to create sources of communal joy and strategies of protection such as avoiding activists and community members’ identification in publications.

Our colleague at Rio de Janeiro State University, sociologist José León Szwako, faculty at the Institute of Social and Political Studies, argued that negationism is not foreign to, but formulated within the realm of science, as a collective investment by concrete networks who dispute the boundaries and scope of scientific discourse, seeking concrete gains, whether material or moral. In those disputes, gender becomes a highly contested issue, for its relevance as a site of regulation, with grave effects on public policy. Therefore we should look for negationism not only in the media and politics, but pay attention to its intellectual and scientific roots.

The audience included researchers, faculty, students from all levels and alumni, as well as activists interested in gender, sexuality, health, fake news and disinformation, online GBV and the current anti-democratic turn. The debate in our session challenged common sense understandings of online violence and highlighted its complexity, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated “infodemic”, as its communicational context was aptly called. The audience came out with relevant information, got their assumptions challenged and acquired new conceptual tools to address pressing issues. All invited speakers knew about each other’s work and, although it took place by virtual means, the debate was an opportunity to get to know each other “in person”. As we all enthusiastically recognised, the talks expanded our own perspectives on political violence, online GBV, the role of gender and sexuality in Brazilian ultra-conservative discourse and on scientific negationism. Plans were made to find more ways of keeping this discussion alive, in the form of future events and publishing opportunities. More live transmissions around similar intersections are planned for the 2021 CLAM debates series, and also at other online forums both during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, hopefully in person physically.

Research question, rationale and objectives

The increasing public legitimation of anti-feminist, anti-LGBTIQ and anti- human rights discourse over at least the past decade in Brazil, by means of moral panics and disinformation campaigns, produced hostility and acts of violence against women and sexual minorities, and towards feminists and LGBTIQ activists in particular, that were capitalised for the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president in 2018. That hostility and that violence are intersectional, in the sense that negative representations of women and of non-normative sexualities and gender expressions are always and primarily conceived within age, class and racialised hierarchies. Social media has been instrumental to anti-rights engagement and the COVID-19 pandemic potentiated their role by increasing dependence on online communication, not only as main or primary, but often as the only available means of socialisation and of access to information. This research aimed at generating a complex understanding of the particular role of social media use and architecture in the production and dissemination of anti-rights discourse, often under the form of hate speech, of its reception and of how the communities that are the targets of that hostility may articulate responses to those forms of violence.

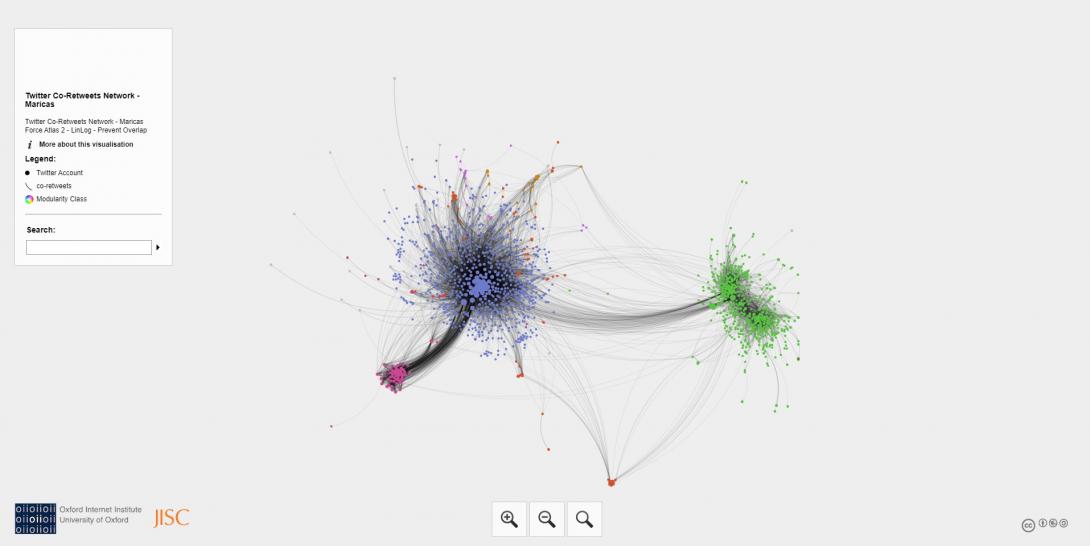

To access the political and technological contexts and the cultural meanings mobilised in current struggles around feminism and LGBTIQ rights in Brazilian social media, we selected cases of “issue networks” in which anti-rights discourse got disseminated, amplified and responded to, triggered by communicational events in the period between the political campaign for the 2018 presidential election and the Municipal elections in late 2020. We described cases in terms of their actors, their language, the semiotics and the social grammar of their messages, and some measure of how social media platform affordabilities shape different forms of engagement with those networks. To assess the impact of this hostile climate, we conducted an online survey that provided some clues about the variety and magnitude of the challenges faced in this context by persons positively engaged with feminism, gender and sexuality issues, their forms of political engagement, their experiences with and individual responses to online violence, and their understandings about its regulation. Finally, to provide a further understanding of the engagement with issues of feminism and online violence, we collected narratives by means of semi-structured open- ended video interviews with a selection of survey respondents.

Feminist methods of data collection and analysis

To construct relevant cases of “issue networks” involving controversies spearheaded by anti-rights discourse on social media, we conducted initial user-end and back-end explorations on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and WhatsApp during 2019 and finally, during the second half of 2020, already into the COVID-19 pandemic, focused on Twitter for its prominent role as forum for political debate. We were already familiar with pro-rights networks and sources, including responses to anti-rights discourse and episodes of homophobic, misogynistic and racist violence from our own previous research and personal and professional and networks. In order to access anti-rights networks, we set out to “lurk” on bolsonarista (supporter of President Bolsonaro) Twitter profiles, tweets and retweets, by constructing an online “research persona”, male, white, vaguely neutral in terms of their politics, who would abstain from engaging in platform interactions other than “following” an initial set of bolsonarista actors, identified based on information from press sources and on front-end user searches. After that, we kept adding accounts suggested by the Twitter algorithm, fed by the research profile’s own behaviour, and by further exploring their connections.

The methodological challenge in our daily engagement with bolsonarista networks was to “learn their language” (their lexicon and social grammar) and etiquette, and to become familiar with their values, norms and cultural references. Our approach to online pro-rights and anti- rights issue spaces actors also meant a methodological distancing from our own preconceptions about both, particularly the latter, so that the partial knowledge to be generated from our situated position could generate more complex interrogations than those coming from our own common sense or as spontaneous responses to the aggressive provocations all too frequent in bolsonarista networks. Making their behaviour and the political challenge it represents the objects of an interrogation, rather than expecting to formulate a direct response to the former, is a methodological step in that direction. Furthermore, in our fieldwork, that engagement could not be actively direct, in the sense of eliciting a response to our inquiries, but paradoxically passive, lurking in their network as anonymous observers.

The materiality of violence in research raises a delicate issue. When researchers immerse themselves in public spaces where violence is exercised acting as “lurkers”, while they may to a certain extent avoid exposure in the sense of not being identifiable, they are still irremediably exposed in the sense that they are vulnerable to the emotional stress that aggressive behaviour primarily produces. Something similar happens when we invite interlocutors, selected precisely because of their vulnerable position, to narrate violences that they dealt with in their past or the ones that they currently face. The framework developed for this project by the Feminist Internet Research Network puts emphasis on care as a meaningful attribute of feminist research. In this research, practices of self, mutual and community care emerged as relevant responses to hate speech, online gender-based violence and hostility on social media. They can be considered forms of political engagement themselves. That finding indicates a path both as a way to deal with the ethical issue of subjects’ and researchers’ vulnerabilities in fieldwork settings, as well as a relevant focus of analytic investment.

The responses to contemporary online challenges related to feminist engagement were the object of two other methodological procedures to add to our composite picture of anti-rights discourse and hate speech in the Brazilian mediasphere: an online survey to illustrate the present variety of forms of online violence, as related to respondents’ political engagement with feminist issues and issues of internet regulation; and a series of open-ended in-depth interviews to discuss similar experiences in their social and biographical context.

An evident limitation to the outcome of the self-administered online survey was the significant homogeneity of its demographics, which were remarkably white, educated, cis-hetero female, and highly concentrated in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area. While it is expectable that the declaration of some sort of feminist engagement or attention to sexuality politics, as inclusion criteria, would invite a largely female sample, and while self-identified gays and bisexuals were not necessarily underrepresented, we were not able to attract responses by persons self-identified as trans, as cis-male hetero or as non-white in proportions sufficient, or an overall sample large enough to make results statistically comparable. We attribute this shortcoming to our institutional identity as an academic unit, to a somewhat surprising locally-driven outreach, and to the almost exclusively white composition of our unit staff and its relatively short history of investment in racial and intersectional issues. Besides raising structural challenges only recently faced by Brazilian academic institutions in terms of affirmative action, this outcome marks the necessity to create formal partnerships with civil society organisations and activist collectives across the country, and particularly with Black feminist and trans collectives and organisations, in order to reach a more diverse and inclusive public. An indispensable condition for that is a pact of equitable protagonism in research. Strengthening those ties became to a large extent impracticable during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, to meet that challenge within this research project, we made an effort to compensate for those limitations and the potential biases they entail, by aiming at a variety of demographics in the selection of interlocutors for our in-depth video interviews.

Ethical framework

The “human” in the human-machine interactions that generate the digital objects we access either by means of front-end immersive observation or back-end metadata collection should not be taken as self-evident, but as the subject of complex mediation, always involving a significant level of indeterminacy. As regards to the confidentiality of that data, the digital objects that we accessed and scrutinised were not only defined as public as a matter of legal regulation (either by platform default or by user’s deliberate choice), but their creators also intended to make them public to the greatest extent possible. Our digital databases gathered, in fact, the traces of online behaviour by human actors who sought their own exposure and the amplification of their messages and of their mediated presence in the public sphere. That also allowed for the ethically ambivalent methodological choice of creating a research profile constructed as an imaginary persona, to conduct “lurking” immersive observation on bolsonarista networks. In that way we expected to somehow “cheat” the algorithm into feeding us selections and suggestions not based on our own personal behaviours, leading us to networks where we might be classified as outsiders, but with which we intended to get acquainted. Another reason for that choice had to do with our research team’s safety. The anonymity of our research profile (traceable only to a mobile line registered outside Brazil and accessed on an anonymised web browser) was a limited yet deliberate means of safeguarding our team members from any exposure in those networks during our fieldwork.

We took measures to preserve the anonymity of survey respondents and interviewees, listed in an Informed Consent Form, approved by our academic unit’s Ethical Review Board. Following institutional guidelines, that consent form also raised the issue of discomfort produced by some questions, particularly the ones that evoked traumatic experiences. That text, whose reading was mandatory before the start of the survey or the interview, reminded the respondent or interviewee that the session could be paused or interrupted at any moment at their will, and interviewers were professionally trained to respond with empathy and care towards interviewees. Following another institutional guideline, a statement in the consent form also speculated about potential benefits brought by participating, raising the possibility that the online questionnaire and the interview might represent opportunities to reflect on the issues addressed by the research. In the construction of the survey instrument and as a guideline for the interviews, particular care was exercised to contemplate and respect all forms of self-identification in terms of gender and sexual orientation, including trans and non-binary ones. All multiple-choice questions offered the possibility of formulating a response “other” than the predefined ones.

Discussion of research findings

When we set out to look at the online dissemination of anti-feminist discourse and the incitement to sex panics in the context of right-wing conservative political campaigning in contemporary Brazil, we asked about the role of misogynistic, homophobic and racist hate speech in relation to anti-rights discourse. As the research progressed, we realised the need to gauge their specificity as a form of political violence, i.e. intended to interfere with its target’s political rights and aspirations, in a context marked by gender, sexuality and racial hierarchies. Furthermore, the climate of public hostility against feminists, LGBTIQ and other human rights movements was key to the rise of public support for the election of Jair Bolsonaro in October 2018 and for his and his allies’ implementation of an anti-rights government agenda thereafter.

Over that period, social media became a laboratory for unregulated forms of violence and conservative pedagogies. The hostility against feminists and LGBTIQ individuals by Bolsonaro and his followers cannot be dissociated from the primary role of the anti-gender and anti-sexual rights agenda of his government. Gender and sexuality are not just in the content of those controversies and the discourse they delineate, but sexual morality and the gendering of self and others operates as a primordial political grammar. Anti-rights discourse and hate-speech configure the preferred political language of bolsonarista attacks against political adversaries that they construct as enemies of nation and family. By materialising the status of sexual minorities as morally inferior, hate speech and prejudice produce forms of material and symbolic violence that reveal social inequalities and the workings of oppression. Their activation as political language in social media aims at the disassembly and reassembly of political identities performed by digital populism.

In response, right-wing anti-gender hostility on Brazilian social media has provoked a collective feeling of outrage about offences made possible by the usurpation of online spaces and rights in strict correspondence with what happens in the state’s institutional sphere under the present government. That is understood as an expression and effect of systemic injustices, of rights being violated. In that context, the increased vulnerability of women and minorities is seen as the result of the formation of a hostile, violent environment, facilitated by platforms that only seek their own profit.

Investigating political issue engagement with digital media means addressing the role of opaque network architectures and the complex mediations of community and personhood implicated in competing discourses and narrative disputes. We paid attention to the engagement by different actors, human and digital, and interrogated the materiality of social media technological mediation. In constructing cases of struggles around anti-rights discourse and hate speech in social media, we sought to interrogate not only an overwhelmingly hostile environment, but also queer and feminist vernacular uses of Twitter and Instagram as ways of inhabiting social media spaces, resisting that hostility and claiming those technologies, languages and spaces as their own.

The revealing of violence as such by denunciation, contestation or irony indicates the subsistence of struggles around the meaning of gender and sexual difference, activated by other audiences. Social media also became the main medium where the social movements and subjects who had gained social recognition and citizenship rights over the long process of democratisation that took place since the 1980s could exercise public forms of resistance. Narratives of suffering and understandings of trauma as signs of structural vulnerability also indicate a collective engagement with a struggle. The search for online well-being is both an intimate and public pursuit, negotiated in close-knit networks that are seldom anonymous. Collective responses to violent acts whose meanings are materially and symbolically shared in and by digital networks represent both challenges and opportunities for feminist networks of resistance and care.

Suggestions and input for advocacy

The itineraries followed by this research project deserves some reflection on a variety of issues, regarding two aspects: one the operative and the other involving theoretical, methodological and ethical issues. Additionally, we address a few advocacy issues.

Research – operational aspects

Institutional partnerships: both the successes and the failures, the felicity of some encounters and the hindrances met for the sustainability of others highlight the importance of:

- The cultivation of strategic, sustainable multi-sector (activist professional and grassroots; fellow academic and non-academic research; educational; expert professional as in data science and design; government; legal; parliamentary etc.) partnerships.

- The capacity to revise the terms of existing partnerships and explore new ones, based on experience.

- Accountability among partners both in terms of tangible (deliverables, labour) and not-so-tangible (trust, engagement, solidarity, encouragement, meaningful criticism) reciprocal commitments.

- Feedback, peer advice and supervision.

Research – theoretical, methodological and ethical aspects

- Unlike gender-based violence, where the testimony and political voice of victims is privileged by activists and researchers alike, regulation debates and hegemonic research approaches to online hate speech have privileged its framing in legal terms. The conclusions reached by this research indicate the relevance of socio-cultural and linguistic approaches. Further explorations addressing hate speech in the context of different disputes and in different media should include anthropological perspectives on social suffering, care, the legibility of state practices, biopolitics and necropolitics.

- The pedagogical role of homophobia, misogyny and class violence in bolsonarista political language can be addressed using the analytical tools of critical masculinity studies.

- Further empirically-grounded theoretical discussions may explore the materiality of subaltern agency in the context of platformised social media and activist responses to algorithmic discrimination and surveillance, from a collective user-centred perspective, as rehearsed in the interpretive sections of this report.

- Further research and theorisation may address shared perspectives and points of friction regarding definitions of feminist research.

- The overall ethnographic approach to mixed methods proved adequate to the feminist perspective adopted in this research, as well as framing neophyte experiments with digital research methods rudiments and survey methodology. However, a more symmetric approach to those methods must be profitable in the sense of allowing a more thorough, thus reflexive, articulation of their perspectives

- Our experience as queer feminist-identified qualitative researchers in two “data sprints” held by academic digital research methods graduate programs raised issues. Firstly, an issue was raised about the mutual translatability of qualitative research questions and hypotheses, as well as the communicability between issue-oriented and method-oriented research. Second, it raised issues about the intersection between gender and sexuality and digitality, and of gender and sexuality in the study of digitality. On a related note, it called for a thorough, systematic, mapping of existing and potential developments in feminist digital methods.

- The ethical issues of safety, suffering, care and embodiment in research on online violence and hate are always delicate subjects and fertile ground for engaged reflection and problematisation.

Policy and advocacy

- This research provides valuable evidence of urgent issues regarding the critical role of social media development, their political economy and forms of regulation in the facilitation of an increasingly violent mediasphere, hostile toward women and minorities. It takes issue with user and enterprise accountability and with the lack of transparency of social media design and architecture, by providing a situated interpretation of the negation of a feminist internet that the unregulated expansion of an extractivist business model in social media design represents.

- When uttered by political leaders and their followers, hate speech represents a singular challenge for regulation debates; in the case of Brazil, on the applicability of existing legislation. The structural dimensions and legal challenges involved in those issues are beyond the scope of this project; but this research highlights the role of violence in general and of hate speech and online violence in particular as the expression of social struggles around the meaning of social difference.

- Policy makers must be open to dialogue with feminist, LGBTIQ, Black and human rights movements for the design of not only legal regulations,but also pedagogical interventions. Most of all, state regulating organs and processes, third sector organisations responsible for internet control and fiscalisation, and corporate digital providers must include community and academic representation in their governance, policy and overseeing bodies.

- Internet users positively engaged with gender and sexuality issues online denounce a climate of hostility toward their convictions and their very existence and highlight the key role of tech experts, legal operators and care professionals to aid internet users subject to different forms of online violence and fatigue. However, that professional involvement must be collaborative, with communities actively involved in the diagnosis of problems. The importance of nurturing networks of feminist resistance and care is always emphasised.