Platforms, Power, and Politics: Perspectives from Domestic and Care Work in India

Domestic and care work industries in India have been the site of rapid platformisation over the past decade or so. Domestic workers are particularly vulnerable and unprotected, which makes their work qualitatively different than most other sectors in the gig or sharing economy.

The objective of the project is to use a feminist lens to critique platform modalities and orient platformisation dynamics in radically different, worker-first ways.

We use a feminist lens to critique platform modalities and orient platformisation dynamics in radically different, worker-first ways.

The project studies the entry of digital platforms into India’s domestic and care work sector. We find that platforms rely on and amplify unequal structures of power that workers already experience. We use a feminist lens to critique platform modalities and orient platformisation dynamics in radically different, worker-first ways.

Hosted at the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), the research was led by Ambika Tandon and Aayush Rathi, with Sumandro Chattapadhyay providing planning, editorial and project management support. Aayush is a lawyer by training, and has been studying the intersections of labour, gender and technology for the past few years. Ambika is trained in media studies and has led the development of feminist research at CIS since 2018. Sumandro, as a director at CIS, contributes to academic and public policy research on access to knowledge, data governance and digital economy.

The Domestic Workers’ Rights Union (DWRU) was a partner in the implementation of the project, as co-researchers. Geeta Menon, head of DWRU, has three decades’ experience of feminist organising with informal sector workers in Karnataka. The research team consisted of G.P. Parijatha, Radha Keerthana, Zeenathunnisa and Sumathi, who were office holders in the union, where they were responsible for organising workers and addressing their concerns.

Research question, rationale and objectives

What impact has the entry of digital platforms had on the organisation of workers and employment relations? What can a feminist approach to digital labour reveal about the dynamics of platformisation in, and of domestic or reproductive care work?

Women, particularly those experiencing intersectional marginalities including caste and class, are overrepresented in the informal work sector in India. Domestic work in particular has historically been stratified along the lines of caste and gender. Digital platforms are increasingly becoming intermediaries in this space, mediating between so called “semi-skilled” or “low-skilled” workers from lower classes, and millions of middle and upper class employers in tier-1 cities. Our project aimed to answer questions such as: What impact has the entry of digital platforms had on the organisation of workers and employment relations? What can a feminist approach to digital labour reveal about the dynamics of platformisation in, and of domestic or reproductive care work?

Our hypothesis was that platforms are reconfiguring labour conditions, which could empower and/ or exploit workers in ways qualitatively different from non-standard work off the platform. In order to interrogate this further, we studied several aspects of the work relationship, including wages, conditions of work, social security, skill levels and worker surveillance off platforms.

Through our study, we discovered the configuration of gender, class and caste relations in the context of platform-mediated care and reproductive work. This included, among other modes, online and offline modes of surveillance of workers by platforms and employers. We also paid particular attention to strategies of collective bargaining and organisation that have evolved in the context of informal reproductive and care work, and their reconfiguration in the platform economy.

Through this project we have sought to generate foundational work on the developments around platformisation and domestic work in the global South. In doing so, we wanted to generate evidence that fundamentally alters the gaze of research in this space. We do so by focusing on women’s precarious work, centring workers in discussions around their experiences of platforms, and building bridges between advocacy, policy and academic work. We also approach change from a bottom-up perspective. By developing resources that are accessible and usable, we have sought to empower workers’ communities to be able to sustain efforts geared towards change even after the end of the project.

Feminist methods of data collection and analysis

We adopted a feminist ethnographic approach to data collection. From June to November 2019, we conducted 65 in-depth semi-structured interviews, primarily in New Delhi and Bengaluru. The majority of these were with domestic workers who were seeking or had found work through digital platforms. We also did interviews with workers who had found work through traditional placement agencies in order to compare our findings, and also with representatives from platforms, government labour departments, and workers’ collectives. Of the workers we interviewed, the majority were women but men were also included.

Interviews in New Delhi were undertaken by the authors, while interviews with workers in Bengaluru were undertaken by grassroots activists in that city, affiliated with the DWRU. This was their first exposure to formal research and the study of digital platformisation.

In implementing the data collection approach, we employed feminist methodological principles of intersectionality, self-reflexivity, and participation. The methodology draws on standpoint theory, which encourages knowledge production that has the lived experiences of marginalised groups at its centre. We were acutely aware of our own positionality as high income, Savarna researchers studying a sector dominated by Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi women from low income groups. This power differential was somewhat softened by involving DWRU through the course of the project. Workers across both field sites were also interviewed in spaces familiar to them, most often in their homes, in languages that they were comfortable with including Hindi, Kannada, and Tamil.

Feminist principles were also instrumental during the data analysis, with focus on intersectionality and self-reflexivity. We highlighted the ways in which inequalities of gender, income, migration status, caste, and religion are replicated and amplified in the platform economy. In particular, we discussed the impact of the digital gender gap in access and skills on workers’ ability to find economic opportunities.

In response to several respondents having had experiences of feeling abandoned by researchers after opening up to them with their personal histories, we are also integrating a feedback loop with workers and unions to disseminate our research.

In response to several respondents having had experiences of feeling abandoned by researchers after opening up to them with their personal histories, we are also integrating a feedback loop with workers and unions to disseminate our research. This is being done through the development of accessible informational resources that aim to enable workers to make informed choices when seeking work through and with digital platforms.

Ethical framework

Our methodology aimed to co-produce research, as far as possible, from the “standpoint” of workers with double or triple marginalities.

A feminist epistemological framework questions objective knowledge “from nowhere”, asserting that all knowledge is produced and received from within a situated context. The “objective” perspective ends up being the default, or that of dominant social groups, which delegitimise non-normative forms of knowledge produced from the perspective of marginalised identities. To counter such objectivist methods, our methodology aimed to co-produce research, as far as possible, from the “standpoint” of workers with double or triple marginalities.

In addition to workers and unions, we also interviewed companies and government stakeholders. By juxtaposing the standpoints of stakeholders that have differential access to power and resources, we were able to expose various conflicts and intersections in dominant and alternative narratives of the functioning of the platform economy. This sometimes required navigating between the positions taken by workers and companies, which we addressed by privileging the messy lived experiences of workers over those of the “sanitised” perspectives of the platform offered by the representatives of the platform economy.

We also encountered ethical challenges, as a result of approaching companies to connect us with workers. Despite our requests to do so, only two of the companies we approached asked for the consent of workers before sharing their information – which raises ethical questions about consent in research and the arbitrary use of information by platforms. We addressed this partly by ensuring that all workers were given sufficient information about the research, including its objectives and outputs, and the option to opt out whenever they felt the need, before further conversations.

In very few cases, we also hired workers directly, towards the completion of the data collection exercise, to find workers on platforms that did not engage with the study. We registered as employers (through paid subscriptions) with marketplace platforms and digital placement agencies in order to get access to contact information of a designated number of workers, and we were transparent with workers about how we had gained access to their information. We employed two workers through on-demand platforms to perform a one-time cleaning service. Both workers were compensated for their time as per the rate calculated by the platform. We approached them after the completion of the work and receipt of their payment to check if they would be interested in participating in the project, to ensure that there was no pressure to participate. Both workers agreed and were put in touch with DWRU researchers to set up interviews.

Discussion about research findings

Heterogeneity and implications of platform structures

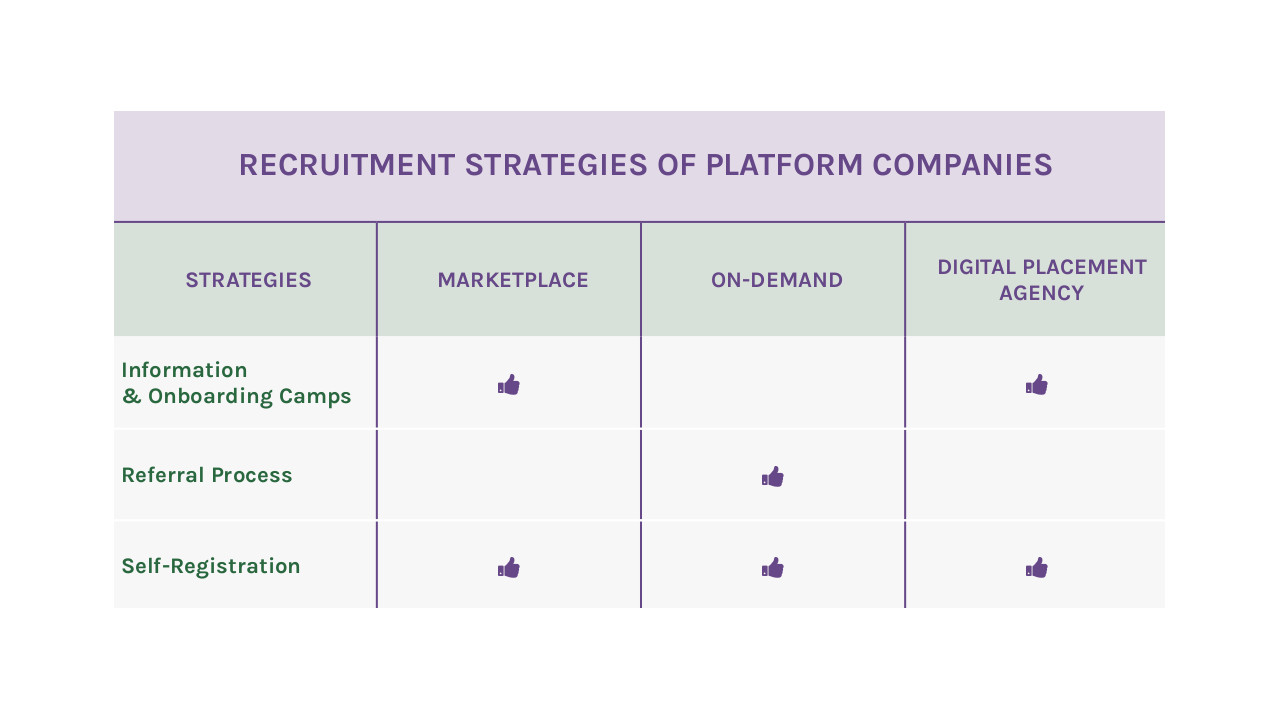

Our typology of platforms mediating domestic work finds three types of platforms:

(i) marketplace: platforms that list workers’ data on their profile, provide certain filters for automated selection of a pool of workers, and charge customers a fee for access to workers’ contact details

(ii) digital placement agency: platforms that provide an end-to-end placement service to customers, identify appropriate workers on the basis of selection criteria, and negotiate conditions of work on behalf of workers

(iii) on-demand platforms: companies that provide services or “gigs” such as cleaning on an hourly basis, performed by a roster of workers who are characterised as “independent contractors”.

When it comes to the role played by platforms in determining employment relations, there is a wide variation within and across platform categories. There are both weak and strong models of intervention. On one end of the spectrum are marketplaces, with minimal intervention in the recruitment process and on the other, on-demand platforms, that exact control over each aspect of work. Digital platforms reconfigure the concept of intermediaries in the domestic work sector, functioning as next-generation placement agencies. All three platform types contain aspects that give workers agency, as well as those that reinforce their positions of low power. Platform design impacts the role that platforms play in setting work conditions but does not determine it entirely.

(Re)shaping the terms of work

Across the three types of platforms, wages are slightly higher than or matching those of workers off platforms. Some marketplace platforms have incorporated features to nudge customers towards setting higher wages, such as enforcing minimum wage standards, or informing customers of expected wages in their locality.

Conversely, on-demand platforms charge a high rate of commission from workers, despite refusing to recognise them as employees. This indicates that this is a misclassification of an employment relationship, given that workers are unable to set their own conditions or wages for work. Despite the high rates of commission and appropriation of labour by platforms, on-demand workers earn higher wages than workers on other platforms. The relatively high wage is a result of marketing on-demand cleaning as professionalised and more skilled than day-to-day cleaning.

On-demand platforms charge a high rate of commission from workers, despite refusing to recognise them as employees.

Tasks in the sector continue to be distributed along the lines of gender and caste, as has historically been the case. Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi women are more likely to take up work such as cleaning and washing dishes, while men and women across castes are equally distributed in cooking work. Women dominate tasks such as looking after the elderly and childcare, as in the traditional economy. Workers in professionalised tasks such as deep cleaning that requires technical equipment and chemicals are almost entirely men.

Digital divides and workers’ agency

We find that workers are primarily onboarded onto platforms by learning about them from other workers, through onboarding camps held by platforms, or offline advertising by platforms. Such in-person onboarding techniques allow workers with no digital access or literacy to register themselves on marketplace platforms and digital placement agencies.

However, we find that low levels of education and digital literacy continue to impact platformed labour by creating a strong informational asymmetry between workers and platforms. For instance, we find that women workers from low-income communities have very little information about how platforms work, causing deep distrust. Workers with digital devices and literacy (and therefore a relatively better understanding of the functionality of the platform), physical mobility and the resources to bear indirect costs that were outsourced to them, were at a significant advantage in finding better-paying jobs. Workers seeking flexibility who were not necessarily dependent on the platform for their primary income were also better placed than those entirely dependent on platforms. Women workers tended to be disadvantaged on all these counts, limiting their agency and capacity to reap the benefits of the platform economy.

Low levels of education and digital literacy continue to impact platformed labour by creating a strong informational asymmetry between workers and platforms.

Across the three types of platforms, systems of placement and ratings add to the information asymmetry, as workers are not aware of the impact of ratings on their ability to find work or charge better wages. Ratings and filtering systems also hard code the impact of workers’ social characteristics on their work. Workers are unable to exercise control over their data, further undermining their agency vis-a-vis platforms and employers. We identified a clear need for collective bargaining structures to protect workers’ rights, although platformed domestic workers remained distant from both domestic work unions and emergent unions of platform workers in other sectors.

Intersectionalities of formalisation

We find that inequalities of caste, class, and gender that have historically shaped the sector continue to be replicated or even amplified in the platform economy. What remains clear is that platforms in the domestic work sector adopt the logics of this sector, more than the converse. Platformisation is conflated with formalisation, and it is within this vector, from complete informality to piecemeal formalisation, that platforms operate. Labour benefits do not take the form of labour protections or welfare entitlements that are the central function of formalisation processes. Instead, the so-called benefits are intended to transform domestic workers to participate within the logics and vagaries of the market.

Inequalities of caste, class, and gender that have historically shaped the sector continue to be replicated or even amplified in the platform economy.

Research recommendations and inputs for policy advocacy

Building on the data collection and analysis from this project, we produced a specific policy paper (forthcoming) that expands the coverage of this work to the South Asian region. This work was supported by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Some of the policy recommendations that we suggest are below.

Recognise and implement labour protections for domestic workers

Domestic workers have historically occupied the most vulnerable positions in the workforce, with limited legal protections. Exposed to the regulatory grey areas that platforms operate within, this doubly exposes domestic workers to precarious conditions of work. Despite an avowed move towards the formalisation of domestic work, platform-mediated labour continues to retain characteristics of informal labour, even heightening some.

If pushed to do so, platform companies can be instrumental in resolving some of the implementation challenges that governments have faced in enforcing legislative protections sought to be made available to domestic workers. Platforms have databases of workers, which can be used to mandatorily register them for social security schemes offered by the government. This data can also be used for better policy making, in the absence of reliable statistics particularly on migrant workers in the informal economy.

Reduce the protective gap between employment and self-employment

The (mis)classification of “gig” work within labour law frameworks is a matter that continues to be hotly debated amongst policy practitioners, legal scholarship, and civil society actors. Three positions, in particular, have been taken – treating gig workers as employees, independent contractors, or occupying a third intermediate category. More recently, there have been some legal victories guaranteeing employment protections and increasing platform companies’ accountability. However, these successes have been more visible in global North jurisdictions.

Regardless of the resolution of these ongoing debates on employment status, labour frameworks should provide some universal protections to all categories of labour. Such protections must include universal coverage of social security, in addition to rights such as the freedom of association, collective bargaining, equal remuneration and anti-discrimination. Policies geared towards achieving this objective would be significant in reducing the protective gaps between different categories of labour, and would particularly help historical and emerging occupational categories of workers such as “gig” workers and domestic workers.

Recognise the specific challenge(s) and potential of platformisation of domestic work

Platforms hold the potential to act as effective facilitators in informal labour markets. Even when they do not replace existing recruitment pathways, they provide alternate ones. Workers were more likely to register on a platform if they had entered the domestic work labour market recently (often driven by distress and migration), or had not enjoyed success with informal, word-of-mouth neworks. However, platforms also heighten labour market insecurities, and create new ones. These potential risks need to be specifically recognised through appropriate frameworks, such as social security, discrimination law and data protection.

Tailor policy-making to platform models

We identify three types of platforms, each of which intervenes to varying degrees in the work relationship. We recommend that digital placement agencies and marketplace platforms be registered with governments and enforce basic protections for workers such as provision of minimum wage, preventing abuse (including non-payment of wages) and trafficking. On-demand companies on the other hand, must be treated as employers, and workers be accorded employment protections including social security.

In addition to rights-based policy actions, legal-regulatory mechanisms geared towards mitigating the precariousness of platform-based work are required. This can take the shape of clarifying and expanding existing legal-regulatory formulations, or preparing new ones. Such policy making should factor in the power and information asymmetry between domestic workers (and gig workers, generally) and platforms.

Further, in the absence of health or retirement benefits, risks and indirect costs of operations are shifted from employers to workers. For instance, workers provide capital in the form of tools or equipment, support the fluctuation of business and income, and can be “deactivated” from an application as a result of poor ratings or periods of inactivity. Any regulation aiming to extend employee status should mandate platforms to support such indirect costs.

Stories from research

Story 1: Radha, about caste discrimination in everyday work

We borrowed from ethnographic methods and feminist principles to design and implement research tools together, with grassroots workers and organisers. The embeddedness of the union researchers in the lives of domestic workers significantly shaped the research approach and outcomes. This enriched the project by aligning the research topics and outputs with the objectives of grassroots organisers from the start, and helped us to identify gaps in our understanding of workers' experiences and perspectives. For instance, instead of asking directly about caste discrimination that workers were facing, Radha suggested asking about manifestations of such bias in everyday workings of the employment relationship. This could be in the form of separate utensils being given to workers, or workers being asked to take different elevators or stairs from their employers. These insights were invaluable in revealing inequalities in relations between workers, employers and platforms that may have otherwise remained hidden from researchers who did not have intimate knowledge of the field.

Story 2: Doing research together, in solidarity

There were several instances that demonstrated the strength of research that is also interventionist and forms real relationships of solidarity with participants, as opposed to maintaining “objective” standards of keeping participants at arms’ length from researchers. For example, Zeenathunnisa and Ambika set up an interview with a worker named Seema whose contact details they obtained through a platform. Seema was a cleaner and cook in Bengaluru, she migrated from her hometown in Assam two decades before. She spoke Hindi and Ahomiya. She was initially very hesitant about speaking to the researchers, and was afraid that any information she gave would reach placement agencies she had worked with in the past. The researchers explained the research objectives to her daughter over the phone, who then convinced her to participate in the study. During the interview, Seema opened up to the researchers about harrowing experiences of exploitation she had faced at the hands of placement agencies, including wage-theft and bonded labour. She also explained that the platform she had registered with had not undertaken any such illegal activities, but had also not been instrumental in finding her work up until that point. Some of the issues Seema was facing, such as a placement agency having taken her identification documents with force, were dealt with by the union on a regular basis. Zeenathunnisa remained in touch with Seema after the interview, and helped her resolve these issues through support from the union, including obtaining new identification documents from the state government.

There were several instances that demonstrated the strength of research that is also interventionist and forms real relationships of solidarity with participants, as opposed to maintaining “objective” standards of keeping participants at arms’ length from researchers.

Story 3: Supporting gig and domestic workers demands in times of COVID-19

We had to contend with the outbreak of COVIDovid-19 mid-way through the project tenure. With the feedback loops baked in to this project, we were astutely aware of the challenges that the various communities of domestic workers, gig workers and their organisers were faced with. In the aftermath of sudden and near-blanket lockdowns, workers were thrust into unemployment in the middle of a public health crisis. With decreased mobility and distancing restrictions, organisers struggled as well. With encouragement from APC, we were able to work with several civil society actors in India to strategise and develop a charter of recommendations that captured specific activities that public and private actors could implement to safeguard the economic and social wellbeing of vulnerable gig workers. These garnered attention within government bodies and platform companies, and we received queries from groups consulting with quasi-government bodies in developing government support packages. We were also able to support evidence-collection activities of domestic worker groups in Bengaluru. Through this, we documented the scale of sudden unemployment among domestic workers, and their struggles to make ends meet. This was well received by the labour officials in the state of Karnataka and the groups received a commitment from the state government to provide emergency economic support.